Posts tagged evolution

mindblowingscience:

A comparison of bat and bird wings reveals their evolutionary paths are vastly different

Bats are incredibly diverse animals: They can climb onto other animals to drink their blood, pluck insects from leaves or hover to drink nectar from tropical flowers, all of which require distinctive wing designs.

But why aren’t there any flightless bats that behave like ostriches—long-legged creatures that wade along riverbanks for fish like herons—or bats that spend their lives at sea, like the wandering albatross?

Researchers may have just found the answer: Unlike birds, the evolution of bats’ wings and legs is tightly coupled, which may have prevented them from filling as many ecological niches as birds.

“We initially expected to confirm that bat evolution is similar to that of birds, and that their wings and legs evolve independently of one another. The fact we found the opposite was greatly surprising,” said Andrew Orkney, postdoctoral researcher in the laboratory of Brandon Hedrick, assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, in the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Continue Reading.

mr-puff:

mr-puff:

vivisextion-typo:

victusinveritas:

@wooftphr

it continues

There is a detailed vocabulary used to describe organisms which defy classification and a system of nomenclature to denote confidence limits on probable or speculative affinities, but they are generally grouped together as “problematica”. A handy grab-bag of misfits that have exasperated or eluded scientists, ready for future generations to have a go at. In museums, problematica specimens reside in drawers and cabinets equivalent to the ubiquitous drawer of odds and sods that most people have in the kitchen.

via https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/jul/26/unidentified-fossils-palaeontological-problematica

“When Gehring injected Mouse PAX6 into fruit fly embryos, the resultant fruit flies had eyes all over where they had been randomly injected, but these eyes were fruit fly eyes, not mouse eyes.”

–http://dark-mountain.net/blog/in-other-tongues-ecologies-of-meaning-and-loss/

Secondary metabolites are heterogeneous natural products that often mediate interactions between species. The tryptophan-derived secondary metabolite, psilocin, is a serotonin receptor agonist that induces altered states of consciousness. A phylogenetically disjunct group of mushroom-forming fungi in the Agaricales produce the psilocin prodrug, psilocybin. Spotty phylogenetic distributions of fungal compounds are sometimes explained by horizontal transfer of metabolic gene clusters among unrelated fungi with overlapping niches. We report the discovery of a psilocybin gene cluster in three hallucinogenic mushroom genomes, and evidence for its horizontal transfer between fungal lineages. Patterns of gene distribution and transmission suggest that psilocybin provides a fitness advantage in the dung and late wood-decay niches, which may be reservoirs of fungal indole-based metabolites that alter behavior of mycophagous and wood-eating invertebrates. These hallucinogenic mushroom genomes will serve as models in neurochemical ecology, advancing the prospecting and synthetic biology of novel neuropharmaceuticals.

via http://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/08/16/176347

Making music with computer tools is delightful. Musical ideas can be explored quickly and composing songs is easy. Yet for many, these tools are overwhelming: An ocean of settings can be tweaked and it is often unclear, which changes lead to a great song. This experiment investigates how to use evolutionary algorithm and novelty search to help musicians find musical inspiration in Ableton Live.

via https://medium.com/@samim/musical-novelty-search–2177c2a249cc

How is Saccorhytus related to humans? Humans are vertebrates and so are one of the major groups that collectively define the deuterostomes, a group that also includes animals that are quite different from humans, such as sea-urchins and sea-squirts, all ultimately descended from an original deuterostome. Our argument is that Saccorhytus is close to this ancestral form, and so is the most primitive known deuterostome.

via https://www.researchgate.net/blog/post/meet-your-earliest-known-ancestor-saccorhytus

The “adjacent possible” is the most salient, most shared and perhaps most important of a cacophony of colorful metaphors about biology, information, and networks offered us by Stuart Kauffman in his seminal “At Home in the Universe”. Kauffman is an American theoretical biologist whose work on the mathematics of boolean networks and the biology of genomic regulatory networks in practice has defined our understanding of both the possible origins of life and of the contemporary dynamics of complex adaptive systems, such as the biosphere and the econosphere at scale. So what is the adjacent possible?

via https://medium.com/@Santafebound/what-is-the-adjacent-possible–17680e4d1198

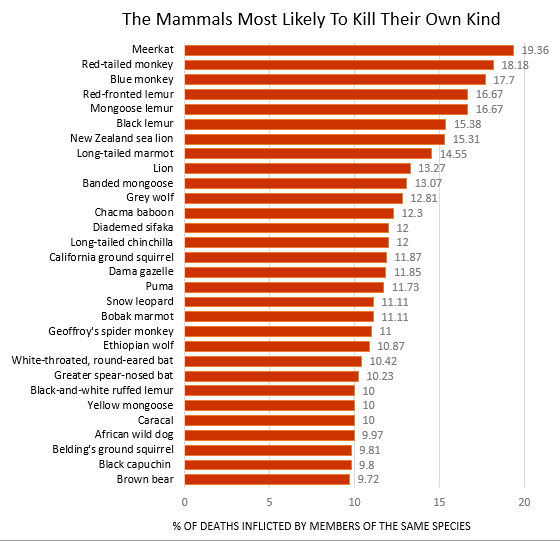

Gómez’s study is the first thorough survey of violence in the mammal world, collating data on more than a thousand species. It clearly shows that we humans are not alone in our capacity to kill each other. Our closest relatives, the chimpanzees, have been known to wage brutal war, but even apparently peaceful creatures take each other’s lives. When ranked according to their rates of lethal violence, ground squirrels, wild horses, gazelle, and deer all feature in the top 50. So do long-tailed chinchillas, which kill each other more frequently than tigers and bears do.

via http://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/09/humans-are-unusually-violent-mammals-but-averagely-violent-primates/501935/

Gómez’s study is the first thorough survey of violence in the mammal world, collating data on more than a thousand species. It clearly shows that we humans are not alone in our capacity to kill each other. Our closest relatives, the chimpanzees, have been known to wage brutal war, but even apparently peaceful creatures take each other’s lives. When ranked according to their rates of lethal violence, ground squirrels, wild horses, gazelle, and deer all feature in the top 50. So do long-tailed chinchillas, which kill each other more frequently than tigers and bears do.

The primates—the order that includes us, apes, monkeys, and lemurs—seem to be especially violent. While just 0.3 percent of mammal deaths are caused by members of the same species, that rate rose to 2.3 percent in the common ancestor of primates, and dropped slightly to 1.8 percent in the ancestor of great apes. That’s the lethal legacy that humanity inherited.

That isn’t to imply determinism. Even within the apes, chimps are notably more aggressive than bonobos, which suggests that group-wide capacities for violence can be tempered by other factors. And history shows that humans have also varied greatly in our violent tendencies. We are influenced by our history, but not saddled to it.

Gómez’s team showed that by poring through statistical yearbooks, archaeological sites, and more, to work out causes of death in 600 human populations between 50,000 BC to the present day. They concluded that rates of lethal violence originally ranged from 3.4 to 3.9 percent during Paleolithic times, making us only slightly more violent than you’d expect for a primate of our evolutionary past. That rate rose to around 12 percent during the bloody Medieval period, before falling again over the last few centuries to levels even lower than our prehistoric past.

The film turns on the visual language of the heptapods, the name given to the aliens because of their seven tentacular feet. In Chiang’s short story, the spoken language looks pretty familiar to Dr Banks; nouns have special markers, similar to the grammatical cases of Latin or German, that signify meaning; there are words, and they seem to come in particular orders depending on what their function is in the grammar of the sentence. But it is the visual language that is at the heart of the story. This language, as presented in the film, is just beautiful; the aliens squirt some kind of squid-like ink into the air which resolves holistically into a presentation of the thought they want to express. It looks like a circular whorl drawn with complex curlicues twisting off of the main circumference. The form of the language is not linear in any sense. The whorls emerge simultaneously as wholes. The orientation, shape, modulation, and direction of the tendrils that build the whorls serve to convey the meaningful connections of the parts to the whole. Multiple sentences can all be combined into more and more complex forms that, in the film, require GPS style computer analysis. The atemporality and multidimensionality of the heptapods’ written language is a core part of the plot. So, could a human language work like this, or is that just too alien?

via https://davidadger.org/2016/09/23/how-alien-can-language-be/

The last drug has fallen. Bacteria carrying a gene that allows them to resist polymyxins, the antibiotics of last resort for some kinds of infection, have been found in Denmark and China, prompting a global search for the gene. The discovery means that gram-negative bacteria, which cause common gut, urinary and blood infections in humans, can now become “pan-resistant”, with genes that defeat all antibiotics now available. That will make some infections incurable, unless new kinds of antibiotics are brought to market soon. Colistin, the most common polymyxin, is a last-resort treatment for infections with bacteria such as E. coli and Klebsiella that resist all other available antibiotics.

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn28633-resistance-to-last-resort-antibiotic-has-now-spread-across-globe/

Biologists study how organisms evolve and adapt to their environments. In the Genre Evolution Project, we approach literature in a similar way. We study literature as a living thing, able to adapt to society’s desires and able to influence those desires. Currently, we are tracking the evolution of pulp science fiction short stories published between 1926 and 1999. Just as a biologist might ask the question, “How does a preference for mating with red-eyed males effect eye color distribution in seven generations of fruit flies?” the GEP might ask, “How does the increasing representation of women as authors of science fiction affect the treatment of medicine in the 1960s and beyond?”

http://www.umich.edu/~genreevo/

Curiosity does not seem to be a fundamental drive, unlike what I am told are the three basic biological drives (seeking pleasure, avoiding pain and conserving energy), so it is probably derived. Curiosity requires a certain energy surplus, since its visible signature is a restless dissipation of energy, but it does not seem directly motivated by energy conservation concerns. So is it derived from pleasure-seeking or pain-avoidance or some mix of the two? Does that make a difference?

http://www.ribbonfarm.com/2013/03/13/the-dead-curious-cat-and-the-joyless-immortal/

Although she writes, “I would not dream of denying the evolutionary heritage present in our bodies,” Zuk briskly dismisses as simply “wrong” many common notions about that heritage. These errors fall into two large categories: misunderstandings about how evolution works and unfounded assumptions about how paleolithic humans lived. The first area is her speciality, and “Paleofantasy” offers a lively, lucid illustration of the intricacies of this all-important natural process. When it comes to the latter category, the anthropological aspect of the problem, Zuk treads more gingerly. Not only is this not her own field, but, as she observes, it is “ground often marked by acrimony and rancor” among the specialists themselves.

http://www.salon.com/2013/03/10/paleofantasy_stone_age_delusions/

RICH AND SEEMINGLY BOUNDLESS as the creative arts seem to be, each is filtered through the narrow biological channels of human cognition. Our sensory world, what we can learn unaided about reality external to our bodies, is pitifully small. Our vision is limited to a tiny segment of the electromagnetic spectrum, where wave frequencies in their fullness range from gamma radiation at the upper end, downward to the ultralow frequency used in some specialized forms of communication. We see only a tiny bit in the middle of the whole, which we refer to as the “visual spectrum.” Our optical apparatus divides this accessible piece into the fuzzy divisions we call colors. Just beyond blue in frequency is ultraviolet, which insects can see but we cannot. Of the sound frequencies all around us we hear only a few. Bats orient with the echoes of ultrasound, at a frequency too high for our ears, and elephants communicate with grumbling at frequencies too low.

http://harvardmagazine.com/2012/05/on-the-origins-of-the-arts

Shaped like a leaf itself, the slug Elysia chlorotica already has a reputation for kidnapping the photosynthesizing organelles and some genes from algae. Now it turns out that the slug has acquired enough stolen goods to make an entire plant chemical-making pathway work inside an animal body, says Sidney K. Pierce of the University of South Florida in Tampa.

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2010/01/green-sea-slug/