Gómez’s study is the first thorough survey of violence in the mammal world, collating data on more than a thousand species. It…

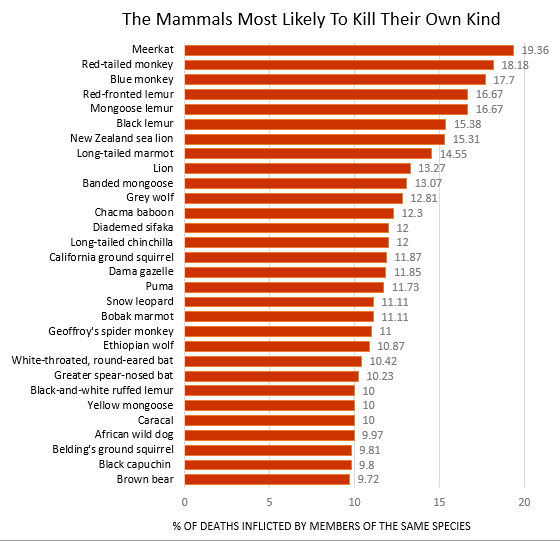

Gómez’s study is the first thorough survey of violence in the mammal world, collating data on more than a thousand species. It clearly shows that we humans are not alone in our capacity to kill each other. Our closest relatives, the chimpanzees, have been known to wage brutal war, but even apparently peaceful creatures take each other’s lives. When ranked according to their rates of lethal violence, ground squirrels, wild horses, gazelle, and deer all feature in the top 50. So do long-tailed chinchillas, which kill each other more frequently than tigers and bears do.

The primates—the order that includes us, apes, monkeys, and lemurs—seem to be especially violent. While just 0.3 percent of mammal deaths are caused by members of the same species, that rate rose to 2.3 percent in the common ancestor of primates, and dropped slightly to 1.8 percent in the ancestor of great apes. That’s the lethal legacy that humanity inherited.

That isn’t to imply determinism. Even within the apes, chimps are notably more aggressive than bonobos, which suggests that group-wide capacities for violence can be tempered by other factors. And history shows that humans have also varied greatly in our violent tendencies. We are influenced by our history, but not saddled to it.

Gómez’s team showed that by poring through statistical yearbooks, archaeological sites, and more, to work out causes of death in 600 human populations between 50,000 BC to the present day. They concluded that rates of lethal violence originally ranged from 3.4 to 3.9 percent during Paleolithic times, making us only slightly more violent than you’d expect for a primate of our evolutionary past. That rate rose to around 12 percent during the bloody Medieval period, before falling again over the last few centuries to levels even lower than our prehistoric past.